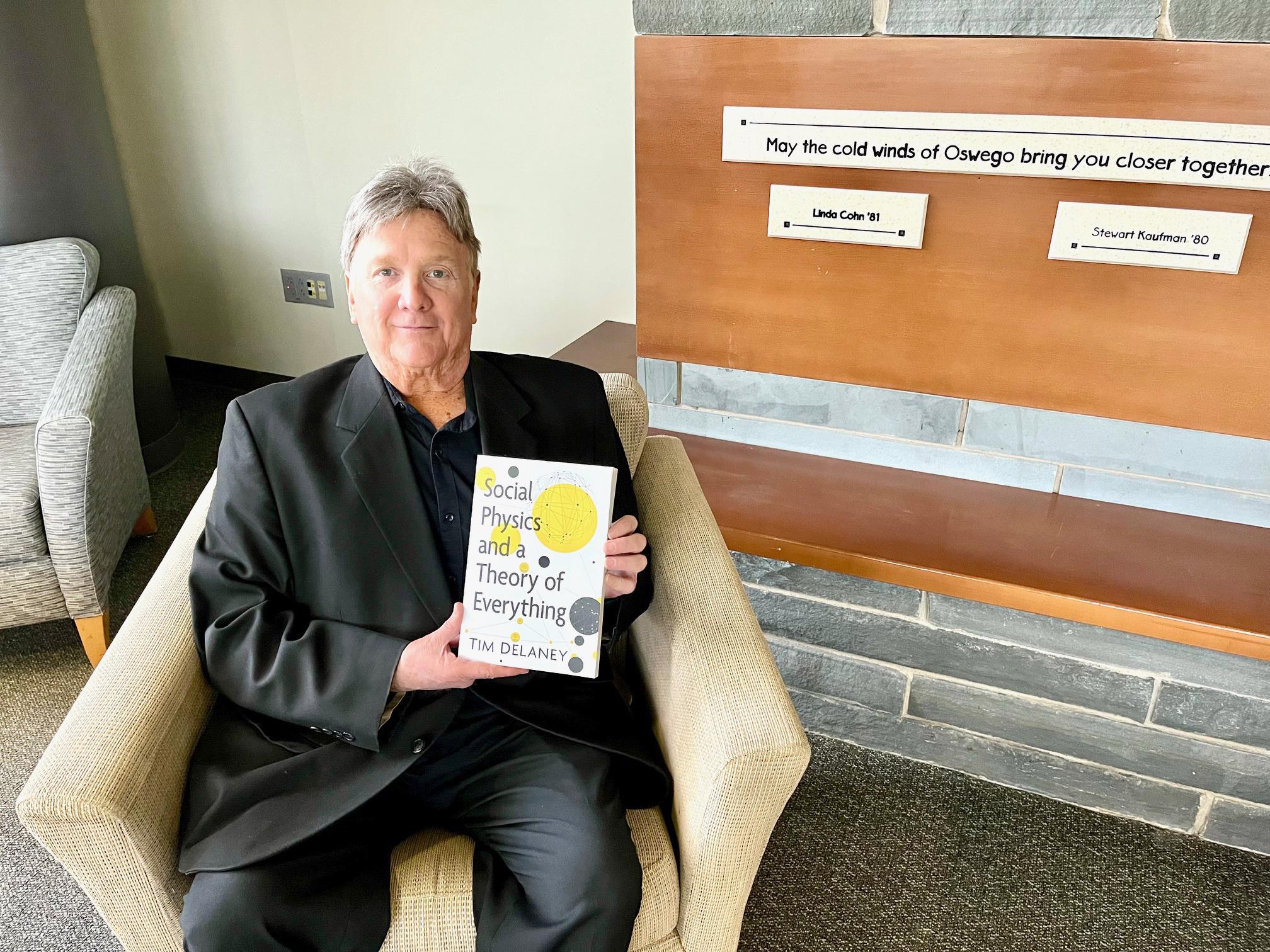

Longtime sociology professor Tim Delaney’s 24th first-edition book, recently published by McFarland, may well be his most ambitious, tackling humanity’s biggest questions by taking on “Social Physics and a Theory of Everything.”

“It’s interesting to me that traditional sociologists study human nature and how that relates to the world around us, and physicists study nature and the universe, but not many people go in depth into how these studies can work together to answer the bigger questions,” Delaney said.

These questions include “What is the fate of humanity?,” “What is the fate of the planet?,” “What is the fate of the universe?” and “When we die, what happens?” While not all of these questions have concrete answers, Delaney posits that one can at least narrow down possibilities by using social physics.

Influential thinker Auguste Comte, who coined the term “sociology,” actually preferred the term “social physics” to describe the discipline as it emerged in the 1820s, known at the time as “positive psychology,” Delaney said.

“Comte really thought of the field as more of a science, and modeled it after physics and related studies,” Delaney said. “He stressed experimentation, gathering data and examining the collected data to study people and humanity.”

Like Comte, Delaney believes that humanity evolved in terms of thought, structure and technology, and this timeline shows in his four sections of the book, each consisting of three chapters:

- Part A – From Early Science to Physics

- Part B – From Early Social Thought to Social Physics to Sociology

- Part C – Physics: Theories of Everything

- Part D – A Theory of Everything from the Social Physics Perspective

The view also incorporates the evolution of artificial intelligence, which Delaney sees as the next significant stage of human development.

“I describe in detail the positives of AI and the negatives of AI,” Delaney said. “The biggest question might be what happens when we reach AI singularity, or when robots become self-aware. I believe it’s not if but when it happens, and how heavily that will impact humanity.”

Theories of everything

The exploration of “a theory of everything” isn’t new, and is something tackled by some of the brightest minds in physics –- but not necessarily with humanity as a large focus of the equation, Delaney said, examining it in the book’s Part C.

Albert Einstein explored a unified field theory in physics using his theory of relativity, Stephen Hawking probed a unified theory on the universe’s origin and fate using quantum mechanics, and more recently, Michio Kaku has tried to develop a unified thesis via superstring theory.

Despite decades as a social scientist, teacher and researcher, Delaney realized that tackling this task would involve learning a whole new field. “I spent about two years immersing myself in and teaching myself the basic theories of physics,” he said.

In addition to providing a great deal of information, the book also offers an on-ramp for people in two fields to better grasp another very important discipline, he said.

“I think a physicist who would like to gain a basic understanding of sociology could benefit from reading this book, as would a sociologist who would like to gain a basic understanding of physics,” Delaney said.

As with all of his writings, Delaney emphasizes making the book accessible and easy to read for those new to the concepts, as opposed to being loaded with jargon and placing a burden on the reader to know everything coming in.

“People who have a thirst for knowledge, people who want to get some answers toward humanity’s biggest questions, and people who are curious to figure out why things happen will enjoy this book,” Delaney said.

Delaney invites anybody interested in the book or topics to join him for a launch party and signing from 1 to 3 p.m. on Sunday, June 8, at Swaby’s Tavern, 6 South St. in his native Auburn.

With a couple of dozen original books, many with multiple editions published, as well as a robust teaching record, this book feels less like the end of a chapter to Delaney than the beginning of another one.

“It’s just another step in what I’ve been doing in sociology,” Delaney said. “For a sociologist to explore physics the way I do is very rare. Perhaps others will follow up on this work to explore it further. And maybe I will as well.”