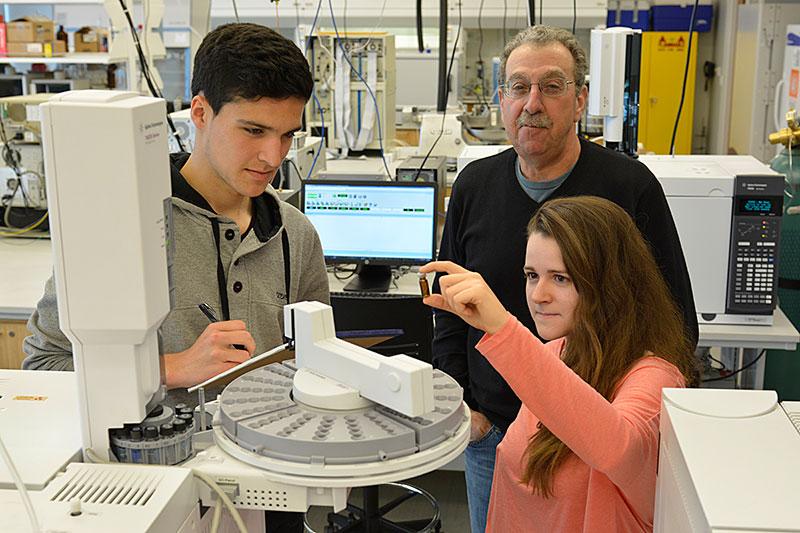

Monitoring pollutants—Working in SUNY Oswego’s Environmental Research Center, junior chemistry major Jesse Mazur (left) and senior biochemistry major Hannah Valentino check a sample of fish tissue bound for a gas chromatograph, which will analyze the sample for chemical compounds. Looking on, Jim Pagano, director of the center, recently learned the college would share in the third five-year grant under the leadership of Clarkson University to monitor Great Lakes fish for pollutants.

Under a $1.5 million share of an Environmental Protection Agency grant, SUNY Oswego and its Environmental Research Center will continue in a research partnership that has documented marked declines in older chemical pollutants in the Great Lakes.

“Most legacy chemical compounds show significant decreases in water, atmosphere, fish and fish eggs,” said Dr. James Pagano, director of the Environmental Research Center. “All the good work of the EPA, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act and the many state agencies have led to significant reductions in those chemicals.”

In its partnership with Clarkson University and SUNY Fredonia, SUNY Oswego will continue to lead the effort to monitor such persistent toxic chemicals as PCBs, dioxins, furans and a long list of other legacy pollutants.

The effort to identify emerging chemical threats will expand under the latest Clarkson-led EPA Great Lakes Restoration Initiative grant, titled “Great Lakes Fish Monitoring and Surveillance Program: Expanding the Boundaries.” The $6.5 million grant, of which Oswego’s $1.5 million is a part, is the third in a series of five-year research grants for the partnership.

The new effort aims, in part, to expand the list of target chemicals, to identify new threats before they become potential health problems for fish, other lake inhabitants and the people in the Great Lakes Basin who consume them.

While a team of Clarkson scientists carries the brunt of responsibility for emerging threat surveillance, SUNY Oswego senior biochemistry major Hannah Valentino has carved out a capstone project, under Pagano’s guidance, to measure levels in Great Lakes fish of a relatively new class of flame retardants called organophosphates. “I’m trying to track to see if these compounds are getting into the environment, and whether their presence is rising to alarming levels of concern,” Valentino said.

Gauging threats

Many of the older flame retardants, such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), have been banned for at least a decade—though only since 2013 for one class—and the Environmental Research Center has shown their presence in Great Lakes fish specimens is decreasing over time. They still show up in fish-consumption advisories issued by state agencies, Pagano said.

Organophosphates have replaced PBDEs in manufacturing over the last 20 years. They are used widely in children’s clothing, upholstered furniture and many other potentially flammable consumer goods. “The harm potential is not as well understood,” Pagano said. “One part of the (research partnership’s) program is to determine toxicity of compounds.”

Dr. James MacKenzie of Oswego’s biological sciences faculty received funding as a collaborator on the EPA grant for work on a lake trout liver toxicology study. He is studying physiological changes in lake trout, a top predator in Lake Ontario, for impacts of legacy compounds such as dioxin-like PCBs on thyroid function, sex hormones and metabolic function. Fish serve as bio-monitors for potential human impacts.

Dr. Richard Back, another grant collaborator from the biological sciences department, received funding under the grant to lead the project’s study of contaminants in entities such as plankton and organisms from near the lakebed in the Great Lakes.

Rigorous standards

The Great Lakes Fish Monitoring Program began in 1980 to address concerns over the declining health of the lakes. The scientists in the Clarkson-Oswego-Fredonia partnership began getting together on smaller projects in the mid-‘90s, Pagano said. The EPA made a major grant to the Clarkson-led partnership in 2006 and again in 2011.

Pagano credited the new grant to the partnership’s consistent on-time delivery of high-quality data, thanks to well-trained staff and state-of-the-art equipment such as gas chromatographs, high-resolution mass spectrometers and ultra-cold freezers for storage of fish specimens.

Andrew Garner, research associate, has primary responsibility for preparation of tissue samples in the Environmental Research Center’s laboratory in SUNY Oswego’s Shineman Center. Garner has worked with Jesse Mazur, a junior chemistry major, since the summer. “We work to keep samples from getting contaminated,” Mazur said. “This is the first place I’ve worked outside of a class lab. It’s been a great learning experience.”

Pagano endorsed the value for student scientists, saying the Environmental Research Center’s rigorous standards make for work that is “tedious, complicated and difficult—but if you can do it, you’re on your way to being a skilled chemist.”