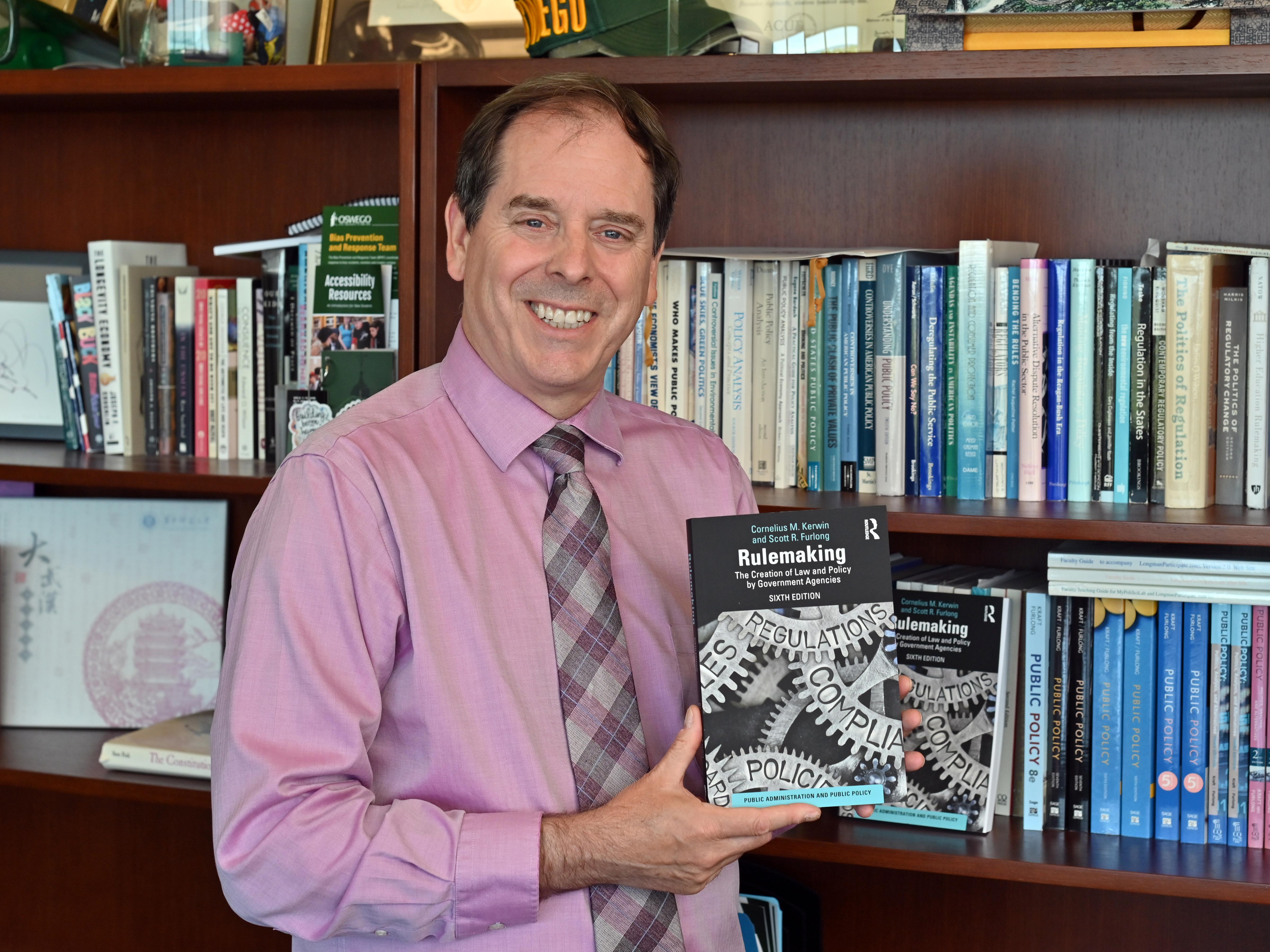

Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs Scott Furlong has co-authored an updated edition of an influential textbook exploring the continued evolution of government decision-making, regulation and enforcement.

Along with mentor Cornelius Kerwin, who published the initial editions, Furlong worked on a lot of changes –- in the real world and text itself –- for the sixth edition of “Rulemaking: The Creation of Law and Policy by Government Agencies," published by Routledge Press.

“Some former students said it was the most important book they used or read and that they want a copy whenever a new edition comes out,” Furlong said. Most of them work in government or government-adjacent roles, so they live what Kerwin –- a former president of American University –- and Furlong cover in these editions.

Furlong first connected with Kerwin, who was starting the series, while the future provost was a part-time Ph.D. student working in the Department of Labor. Kerwin introduced Furlong to an opportunity in the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and they stayed connected.

“I was in a branch of the EPA that managed rulemaking, and he consulted with us on the topic,” Furlong said. “I did some initial research on how agencies do rulemaking, and compiled some statistics and research that were used in early editions of the book."

That opportunity, and discussions with Kerwin about how this was an area that didn’t get a lot of academic attention, led to Furlong working on the topic for his dissertation. The success of the first edition of the book bolstered the need for more research.

“When Kerwin published the first edition, it was the first book on rulemaking from a public policy perspective, not a legal side,” Furlong said.

By the fourth book, Furlong came aboard as a co-author, as Kerwin had become president of American University and Furlong published his own work on rulemaking and could provide additional insights.

“He’s still the main author, but with every edition, I’m doing a little bit more,” Furlong said. “It continues to be a rare look at rulemaking from the public policy side.”

Changing landscape

This edition was a pretty significant reorganization with a couple of new chapters. Much has changed – and continues to do so – since the publication of the fifth edition in 2018.

“The biggest changes involved Supreme Court rulings, in terms of how regulatory agencies were allowed to make rules,” Furlong said. “Previously, if Congress was silent or unclear on its legislation, the courts would typically defer to the agency’s interpretation ruling.”

More recent Supreme Court decisions have rejected this perspective and, in its place, state that justices should be determining the appropriate legislative interpretation.

“This decreased the power of the agencies to interpret laws and put the ball, some would say, back into the courts, which potentially could lead to a significant number of legal challenges in existing rules,” Furlong said. “We also had to incorporate the perspective of how different presidents may choose to use (or not use) regulatory power, as that has a great impact.”

Furlong also pointed to changes in public comments on agency operations, related to technology. “Thirty years ago, it was more difficult to make comments or to find them for research, but now everything is electronic, so it’s easier to submit and find, but also more voluminous,” Furlong said.

With the advent of artificial intelligence, this means people can use ChatGPT to file similar or the same comments under different aliases, but agencies also can use AI to take 1,000 comments and come up with the top themes, he noted.

Donald Trump’s first presidential administration led to different deregulatory stances that impacted the topic, and the writing was mostly complete before Trump’s second oath of office in January 2025.

Given all the changes in regulations in the first months of Trump’s second administration, the authors are considering putting an addendum or something easily accessible that can cover any parts that might become out of date sooner rather than later.

“We do try to make it accessible, but it’s probably something written more for upper-division undergraduate or graduate-school audiences in terms of students and faculty,” Furlong said. The book proves most useful for those in the fields of political science, public administration, and public policy, especially people studying agencies and bureaucracy.